If the Conservatives can get their Communications Machine working, the "Intensity" versus "Absolute" facility level cap on emissions would be a major loser for the Liberals as a campaign issue.

A cap and trade regime that has only absolute emission limits, established only through a quota allocation, delivers unprecedented market power to the highest emitting market incumbents at the expense of low emitters and market entrants. While Quebec does not understand this yet, the case is easily made. If the Liberalss make "absolute vs. intensity" a campaign issue and promote a quota auction-based mechanism to establish absolute limits, the Conservatives can KILL the Liberals in Quebec with a well-designed communications plan.

It Goes Like This

The feds establish an absolutely fixed national Greenhouse Gas (GHG) quota supply. They decide to auction 100% of the quota, every year. We had the first auction last Thursday. Imperial Oil secured triple the GHG allowance supply that they need to continue to operate Syncrude and their refineries on a Business as Usual (BaU) basis, but Hydro Quebec was outbid and comes home short of allowances. Hydro Quebec now has to buy allowances from American Electric Power (another company that was successful at the auction) and Imperial Oil to continue to operate the provincial utility’s highly efficient gas-fired power generation capacity. Cap and trade is dead on arrival.

Quebec cannot afford to stay in a Canada that imposes any national GHG quota regime and trading rule on the Provinces. Period. Quebec cannot afford to allow the feds the right to auction quota, even if the feds promise to transfer all auction funds to the Province in which successful bidders are located.

And Quebec needs any federal standards to be intensity-based. If the Quebec legislature was operating rationally, its members would threaten to constitutionally challenge any federal regulation that imposes absolute GHG limits at the facility level. While the Quebec legislature is not operating rationally now, federal politicians can speed them up the learning curve by walking around the province with the "plant list".

The feds can assign intensity limits to sectors and facilities and can only make any combination of those limits acceptable to provinces if:

- Provinces have the discretion but not the obligation to assign absolute limits to the same facilities and

- Provinces have the discretion to assign different intensity limits than the feds prescribe under the condition they can demonstrate that it is reasonable to forecast that the Province’s proposed allocation of limits/entitlements will achieve reductions, over time, comparable to those that would be achieved through direct implementation of the federal formulae.

This is hard stuff to work through in hypothetical contexts. But all federal politicians need to do is campaign through Quebec and southern Ontario with the major emitters’ plant lists in their hands, pointing out the implications of any Liberal cap and trade or carbon tax proposal for individual plants and ridings.

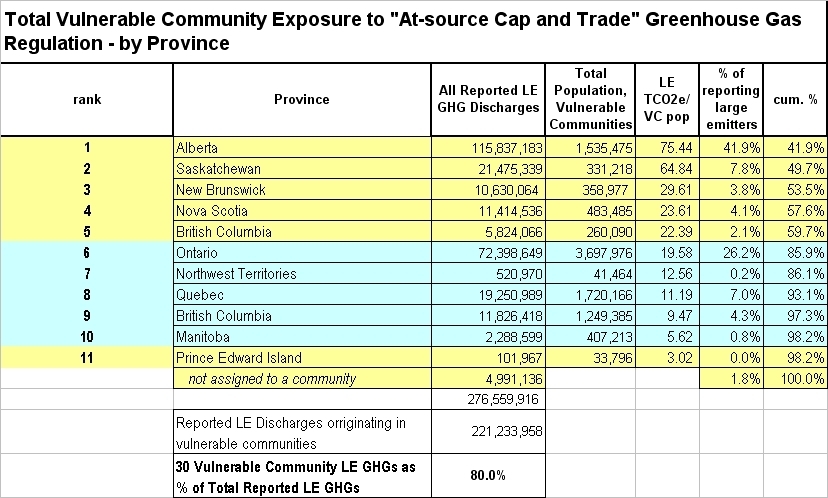

If I define "community" as a federal riding, and a "vulnerable community" as one where a dominant proportion of the voting age population relies on a large emitting source for direct and indirect income, the Large Emitter’s plant list tells us that "cap and trade" and/or carbon tax vulnerable communities are distributed, by province, as in the following table. While Ontario and Quebec only rank 6 and 8 on the province list, look at the sizes of the vulnerable voting age populations for those provinces, compared to the populations whose employment is at risk in the west. Note: LE TCO2e/VC pop" in the heading for column 5 below means "Large Emitter GHGs per registered voter in climate change regulation vulnerable communities.

Specifically, the 30 ridings most economically vulnerable to quota-based GHG management and market control are as follows. This looks to me like 10 Liberal seats that the Cons can win back with an informed campaign. However, I don’t see many Conservative seats open to Liberal acquisition on this same list. Don’t know if either of the Liberals or Conservatives are on top of this, but if the Liberals are on top of this they would just be stupid to bet that the Cons are not.

When we get past the high level rhetoric and down to the facts of the matter, the Canadian operations of 10 corporate entities account for 52% of reported Large Industrial Emitters’ GHGs and only 25 corporate entities account for 76% of reported facility level GHGs. Any serious GHG management plan has to look specifically at the circumstances and development plans of these corporate entities (perhaps in the way that Massachusetts law does for its large emitters) and make sure that any rules we promulgate are both fair to these asset owners and other Canadians and will result in physical changes in the plants these companies operate.

Note that this is not a west-only list. There is not enough GHG inventory left for these corporations to comply through offset purchases for the next 10 years. If we build a GHG regulatory structure that affords them such an opportunity it is, by definition, a regulatory structure that will fail to cut Canadian GHGs, absolutely, by at least 17% by 2020. And if we fail to implement a regulatory strategy that can be reasonably forecast to deliver such an outcome, as soon as such a finding is published by the US EPA then all Canadian energy, building product and food exports will be vulnerable to US , European, Japanese and South Korean tariffs.

I should note that this list reflects GHG reporting only for facilities that discharge more than 100,000 TCO2e per year. However, when we reduce the reporting threshold to, say, 10,000 TCO2re/year (the US EPA-proposed reporting threshold) there are only small ranking changes in the following list, because all of the operators of the largest emitting facilities own plants that are captured by the lower reporting threshold. There are also only small ranking changes in the vulnerable community list. If anything, Ontario and Quebec (along with BC) communities rank higher in vulnerability when we lower the reporting threshold.

Driving down to local detail

When we drive down to narrower definitions of "community", we identify more extreme GHG regulatory risk differentials. As noted above, I used federal electoral ridings to identify "communities as risk" in the above tables. What happens when I shift the definition of "community" to smaller provincial electoral ridings? (I think ridings or economic development regions are better definitions of "community" than metro areas because many people cross metro areas for work. In rural Canada, over 60% of workers leave their metro area for work every day, but most rural Canadians work within their provincial electoral area.)

Now, back to "intensity" versus "absolute"

Every "Successful Cap and Trade" Regime Uses Intensity Limits to Drive the Reduction Schedule

Every existing and relatively "successful cap and trade regulation" in US history assigns at least 2 limits to regulated sources: an absolute limit and an intensity limit. The first intensity limits in existing US regulations are defined in emissions/MM BTU heat input terms Then, in many but not all cases, the facilities’ operating permits include additional limits: emissions/unit of output, emissions/hour of operation, etc. One of the reasons that the EU CO2 ETS is such a failure is that EU rule-makers failed to grasp this most important aspect of US cap and trade.

In the EU rule-makers’ defense, part of the problem is that a good percentage of the US "experts" on "cap and trade" are policy wonks who have never, ever looked at a US operating permit. In the US regulatory system, the legally binding facility limits are embedded in permits. Everything is embedded in permits, if the regulation is enabled by the US Clean Air Act. Permit administration and SO2/NOx market administration are in two different and unconnected locations in the US EPA.

It surprised me to learn, in the late 1990s, that many of the NRDC, Pew and other lobbyists had never looked at or considered the implications of the terms and conditions in operating permits and were only familiar with the administration of the allowance market system. But when the US Congress approved the Acid Rain cap and trade rule, the first specification they wrote was a requirement that affected facility operators apply for permit amendments. If it does not say in your permit that you have to hold allowances, you don’t have to hold allowances. The fact that you now have to hold allowances does not eliminate your obligation to comply with the operating limits outlined in the permit.

In every existing case, the regulated facilities shall not exceed any of the binding emission limits. Most (but not all of the time) the emissions/MM BTU heat input limit is the reduction driver, and the absolute limit equates, roughly, to the estimate of facility emissions after an equipment failure at the beginning of a permit term. (Since the intensity limit can decline over the permit term, the absolute limit embedded in the permit can be 30%+ higher than the intensity-based maximum allowable emissions by the end of a 12 to 16 year permit term). In the US electricity market, in most states the operators also must comply with sulphur content limits (which are intensity-based) for the coal they take into their plants.

Every generating unit that is covered by the US Acid Rain Program includes multiple limits, and no operator can exceed any one of the permitted limits no matter how many SO2 allowances they might have in the bank.

It is not possible to build a cap and trade regime with any environmental integrity without intensity limits. That is why I have always been very shocked at the Canadian ENGO community’s opposition to intensity targets. The ENGO community erred in a big way when they launched the PR campaign that pits intensity against absolute targets. All along, they should have argued intensity AND absolute targets are necessary. They would know this if they actually read any of the over 40 existing cap and trade rules operating in the US air, water and wastewater markets, all of which have both limits.

Because the intensity limits define the emission reduction schedule, it is essential to prescribe the intensity limits first. I might be proved wrong, but I think that Environment Canada officials now understand that it is essential to incorporate intensity limits in any regulation in development. It is essential that our regulatory go back and develop intensity limits to make any Canadian "cap and trade" proposal work. But I do not perceive they are talking about intensity limits and no absolute limits. They are (or at least should be) talking about both, where the absolute limits are slightly higher than and derive from the intensity limits.

The annual absolute emission limits that are included in US facility operating limits are overall market governing limits. While facility operators focus on the generally more stringent intensity limits for operating purposes, regulators know that the maximum aggregate discharge from the regulated sources will not exceed the sum of the absolute limits. Actual aggregate emissions are almost always about 15% below the sum of the absolute limits in these markets, because the regulated entities will only use their absolute annual limits for short operating periods while they are addressing equipment breakdowns.

Why Are Intensity Limits So Important?

"Cap and Trade" is a simple quota-based supply management. It works just like dairy or chicken quota or municipal taxi license regimes. In every other existing Canadian (and long-standing global) quota-based supply management market, it is most often the case that 100% of the quota is auctioned. But only entities with "quota licenses" are permitted to participate in the auction. Only entities that actively operate dairy farms, for example, qualify to have dairy quota licenses.

Among other things, the auction rules also only permit each license-holder to bid one price at each quota auction—none of this multiple cascading bid stuff that you see in RGGI or the US SO2 auction. In the dairy market, licensees pay the price they bid for quota, while in most emission markets—as in electricity markets—all successful bidders pay the same price the last winning bidder pays for quota.

When you elect to build a market where every bidder pays the lowest successful bid price, and you allow every market participant to make multiple bids, you inevitably deliver market power to the parties with the most cash-flow—potentially at the expense of the parties most likely to bring innovation to the market. The richest parties then hoard their quota (only "leasing "quota through swaps) to block new entrants. The badly designed quota regime enables them to drive market prices up while eliminating new market entrants. Inevitably, governments have to follow-up their introduction of quota-trading regimes with (1) border tariffs blocking lower cost imports and (2) price controls to mitigate the market power of the quota holders.

The US SO2 and Los Angeles RECLAIM market designers clearly understood these issues. The designers of these two quota markets used different approaches to mitigate them, and the difference in outcomes is worth paying attention to.

Acid Rain/ SO2 Market: Gettting it Wrong

The EPA designers of the SO2 market decided it was essential to maintain the binding intensity limits in cap-covered generation unit operating permits as a means to limit the market power of incumbent quota holders. If no facility operator can exceed their permit-based intensity limits, the designers believed, they had adequately limited the financial gains to market incumbents from quota banking and hoarding. They were wrong, however.

Under the Acid Rain rule, starting in 2000 every developer of a new power generation unit gets NO free allocation of SO2 quota (the 110 oldest US generating units still receive just under 5 million free SO2 allowances each year through 2030), and they are obliged to buy SO2 allowances from the market or government auction to cover 100% of their new plant SO2 emissions—even though the new plants discharge, on average, about 10% the SO2/MWh that the 110 oldest plants are permitted to discharge.

In fact, the owners of the 110 oldest generation units in the US received their free SO2 allowanced entitlement for a 30 to 35 year term even after they permanently shut down the unit to which the allowances were first allocated. If you go through the US SO2 market data, you will see that since 2000, no market incumbent corporation has sold SO2 allowances to any new market entrant. The incumbents control what new plants get built, through their allowance management practices. The apparent "market price" of SO2 allowances is irrelevant to US utilities. That they can hoard their allowances to block new entrants is most important.

Most brokers argue that the quota instrument and ex-ante annual deposits of quota in plant accounts is necessary to give the market the certainty they require regarding quota supply. This is complete bunk. If you go to review the allowance holdings report, you can look up the free US SO2 allowance entitlement by plant, by year, through 2039. Without any quota, the SO2 regulation that is reflected in this allowance entitlement table provides more certainty regarding future supply than exists in any physical commodity market (especially given that the SO2 rule stipulates that entities that shut down plants still receive the listed SO2 allowances after the shut down). The information at this site also means that new market entrants can easily identify allowance holders without the help of brokers.

In theory, new market entrants can get SO2 allowances at the annual EPA SO2 auction, either directly or through brokers. But if you look up the auction results for many years, you see that incumbents (and brokers acting for incumbents) tend to clean up at the auction. The only good thing about the Acid Rain allowance auction is that bidders pay the price they bid for the allowances they take home from the auction. This is not how traditional electricity markets or the RGGI auction works.

We should never, in Canada, implement any auction that is modeled after the RGGI design. In RGGI, every bidder pays the lowest successful bid price for all of the allowances they take home. So bid prices simply create a distribution ranking. Operators of old, written-off coal plants can bid very high prices to stake out high rankings for large bids without any risk that they have to pay that price for allowances. Operators of new, highly efficient and higher operating cost plants cannot afford to bid high allowance prices because that would run them into operating losses. So the system guarantees that the oldest, dirtiest plant operators get all the allowances they need at the highest price the most efficient cleanest operator can afford to pay.

This is a very stupid system unless, of course, your only objective is to subsidize the continuing operation of the oldest, dirtiest plants. And this is happening. Look at the age distribution of the oldest US plants that sold power in 2007 and 2008 in the table below. The US Acid Rain program’s quota allocation and trading rules have actually extended the operating lives of the nation’s oldest and dirtiest plants while impeding investment in "clean coal" technology. This is, in fact, why the EPA felt the need to introduce the CAIR regulations in 2005 (which the US court vacated in 2007) and why Congress is taking a very different—even more "intensity-based" approach to "cap and trade" in the developing climate change legislation.